If, in Mitchell’s reality, blacks were free but unequal, in her book they are flat and one-dimensional, enduring the cruellest sentence a novelist can impose. The defeated south could not revert to the days of slave plantations, but via segregation it could confine its former slaves to a social position where they could not fraternise, shop, eat, or use the same drinking fountains as their former owners. If the romanticism of Mitchell’s novel was a beautiful, literary reconciliation with defeat, segregation could be considered its ugly, legal twin. Mitchell lived at a time when her beloved Georgia enforced discriminatory Jim Crow laws that mandated the separation of blacks and whites in schools, trains and most public places. If Gone With the Wind was inspired by Mitchell’s life, it is worth noting what was left out. On record, Mitchell admitted only to the likeness of Prissy (the slave who helps deliver Melanie’s baby) to a servant named Cammie. Both enjoyed the hedonism of prewar gaiety and ill-advised marriages to rakish men. Also like the actual Peggy, the fictive Scarlett is tormented by unrequited loves. As Edwards tells it, the protagonist was originally named Peggy, like its author. Gone With the Wind, however, takes liberally from its author’s life. But a novel can sanitise entirely the inequities of real history.

Writing, after all, is the author’s means of retrieving moments, and even worlds, made remote by time or tragedy. One can see how the tales of a glorious past influenced Mitchell’s novel. This was almost true, as Anne Edwards points out in Road to Tara, her biography of Mitchell: while the young Margaret was born long after the war was over, she was reared on a solid diet of civil war reminiscence on their Sunday afternoons, her family devoted themselves to the stories of veterans turned bards. Such is the magnificence of Mitchell’s historical revisionism that many contemporary readers would assume that she lived through the civil war herself, felt first hand the loss of dignity that came with defeat. The homage from the American south is well deserved Mitchell gave her readers an indomitable southern heroine, reframed slave-owning plantations as beloved homesteads and reduced the complications of race to huggable slaves who adore their owners. In Atlanta, the house where Mitchell lived and wrote Gone With the Wind in is now a museum devoted to her memory.

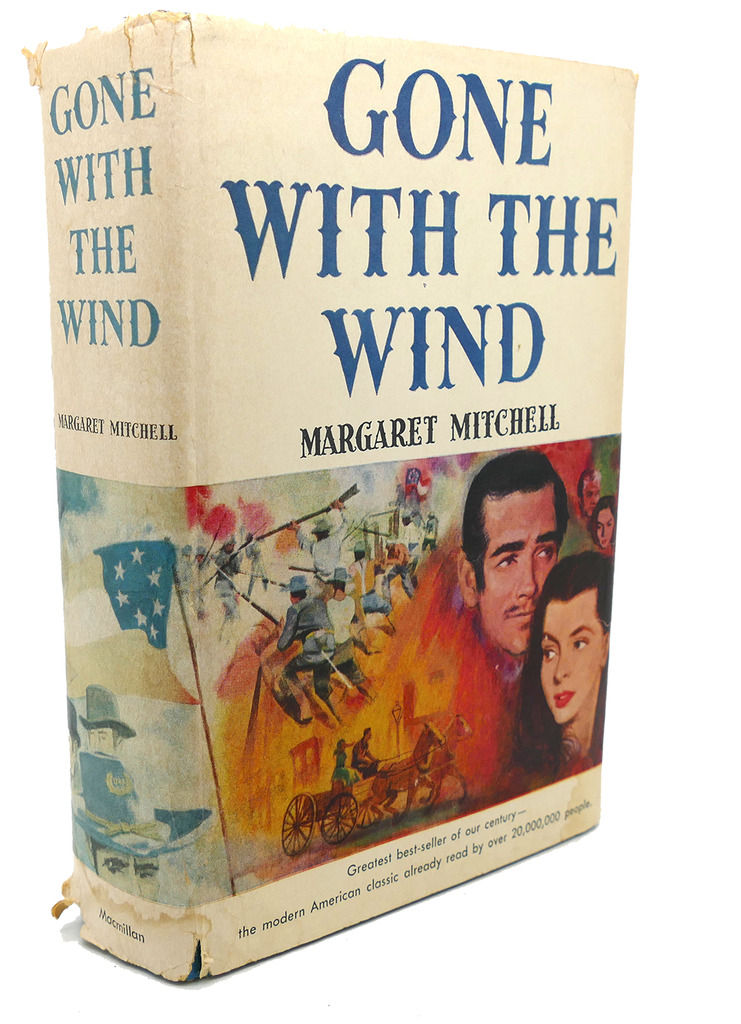

Nor is its appeal is limited to the English-speaking world it is available in Amharic (Ethiopia) and Farsi (Iran) and in 2012 the book was translated and published in North Korea, where the themes of war, hunger and famine resonate with local readers. Today the book retains its acclaim, with the 1939 film starring Vivien Leigh only adding to its popularity. Photograph: Courtesy Everett Collection/REX

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)